(The article is authored by Dr. Anuj Tiwari, a migration researcher; Anurag Devkota, a human rights lawyer; and Bhim Shrestha, the Executive Director of Shramik Sanjal.)

The democratic power centers on people’s needs, and once again the statement holds true in Nepal. The Gen-Z-led seismic uprising toppled the government in just 27 hours; however, the turbulent transition awaits Nepal on every front of governance. The echoes of a Gen-Z-led protest resonate in the fresh mandate of the interim government, yet amid this triumph, a glaring irony persists: Nepal’s democracy remains territorially myopic. At the very moment when a generational recalibration of power demanded accountability, a significant number of Nepali citizens were denied their right to vote—not by force, but by distance.

For years, the implementation of Out-of-Country Voting (OCV) has been a classic Nepali case of delay and denial. Despite the Supreme Court’s 2018 directive ordering the Election Commission of Nepal to execute OCV, the Nepali diaspora remains in democratic exile. Interestingly, the interim Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Sushila Karki, was the Chief Justice when the writ petition was filed in April 2017 by the Law and Policy Forum for Social Justice (LAPSOJ). However, the verdict came in March 2018, after her tenure had ended.

The Election Commission subsequently included OCV in its 2019–2024 Strategic Plan, but progress stalled amid COVID-19 chaos and a lack of political will. Perhaps the major political parties in Nepal feared a huge, unpredictable bloc of voters demanding better consular services, safer migration channels, opportunities for economic investment, and the potential to disrupt entrenched patronage networks at home.

The recent Gen-Z-led movement has fundamentally altered that calculus. The interim government, born of political upheaval, now operates on a clear mandate to hold elections within six months. In this new political space, the current Home Minister, Om Prakash Aryal, who also holds the portfolio of the Ministry of Law, has vowed to implement diaspora voting. We hope this no longer remains a mere promise, akin to past governments’ or political parties’ demagoguery. If realized, it would be the “icing on the cake” of a revolution that must prove it serves all citizens, regardless of geography.

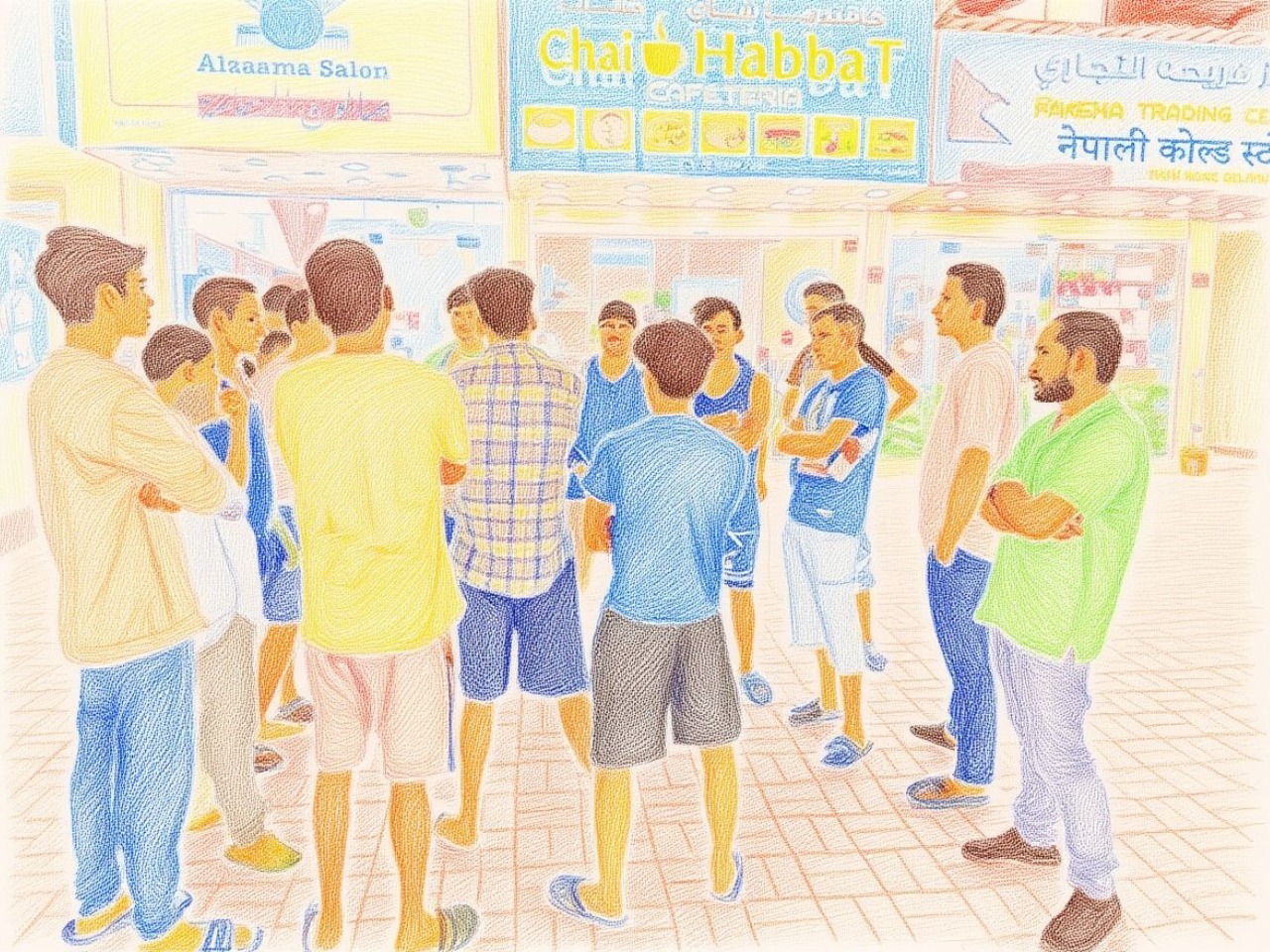

Fueling the urgency to implement OCV, LAPSOJ and Shramik Sanjal conducted a survey among 6,485 migrants across seven countries (the Gulf Cooperation Council and Malaysia). The survey, conducted from July 14 to September 7, 2024, via Google Forms disseminated by volunteers of Shramik Sanjal, offered a searing glimpse into the perceptions of disenfranchised citizens. It captured not just statistics but also grave injustices. Particularly concerning was that 67 percent of respondents aged 18 to 24 and 71 percent of respondents aged 25 to 31 were not aware of the Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling to execute OCV. Yet a majority of this age group fall into the Gen Z category, who were instrumental in changing the regime at home. However, 93 percent of the total respondents were eager to vote, with 83 percent driven primarily to uphold democratic rights.

The data also provides a roadmap for the Election Commission. An overwhelming 92 percent of respondents favored electronic or internet voting—solutions that are secure, efficient, and aligned with 21st-century democracy. Similarly, respondents highlighted technological complexities and legal barriers in host countries as challenges, but these are solvable technical problems. Diplomacy must now become a tool of democratic empowerment, where Nepal’s foreign missions act as a catalyst and engage with host nations to ensure voting proceeds smoothly and securely.

This perception survey is a clarion call from the margins, colliding with Nepal’s democratic fate. Karki’s interim regime has a unique opportunity to champion diaspora voting as it inherits the Election Commission’s stalled 2023 Election Management Act—Clause 22 for diaspora data collection and Clause 204 for in-person voting in diplomatic missions (for proportional representation, for now). By executing diaspora voting, the government can forge a natural alliance with a young, engaged, and digitally native demographic. Indeed, the youngest migrants, aged 18 to 24, were the most registered to vote and the most confident in the feasibility of OCV. They are politically conscious, eager to contribute, and the overseas embodiment of the generation that just reshaped Nepal’s politics.

The toppling of the old government was a message that Nepal’s democracy could no longer be a passive inheritance; it must be an active and living practice. Extending the franchise to the diaspora will lift Nepali citizens from mere observers to a force upholding accountability and good governance. It can be a move that not only corrects a historic injustice but also injects a new wave of energy and accountability into Nepal’s political process. As we stand at this rare inflection point, the mandate is clear: build a democracy that leaves no citizen behind, whether they are in Kathmandu, Kuala Lumpur, or Doha. Let March 2026 stand as proof.